Inventions Of The 15th Century

| Four Nifty Inventions | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

V major steps in papermaking, outlined by Cai Lun in AD 105 | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 四大發明 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 四大发明 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | four not bad inventions | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

The Four Great Inventions (simplified Chinese: 四大发明; traditional Chinese: 四大發明) are inventions from ancient China that are celebrated in Chinese civilization for their historical significance and every bit symbols of ancient China's advanced science and engineering science.[one] They are the compass,[2] gunpowder,[three] papermaking[4] and printing.[5]

China held the earth's leading position in many fields in the study of nature from the 1st century BC to the 15th century Advert, with the four great inventions having the greatest global significance.[half dozen]

These iv inventions had a profound bear upon on the development of culture throughout the world. However, some modern Chinese scholars have opined that other Chinese inventions were perhaps more sophisticated and had a greater impact on Chinese culture – the Four Nifty Inventions serve merely to highlight the technological interaction between Due east and West.[seven]

Evolution [edit]

"The 3 Groovy Inventions" was showtime proposed by the British philosopher Francis Bacon, and later by Walter Henry Medhurst, Karl Marx and other scholars agreed.

Printing, gunpowder, and the mariner's compass were brought to Europe by Arab traders during the Renaissance and Reformation. Bacon, a leading philosopher, politician, and adviser to King James I of England, wrote: "It is well to observe the force and virtue and consequence of discoveries. These are to be seen nowhere more than clearly than those three which were unknown to the ancients [the Greeks], and of which the origin, though recent, is obscure and inglorious; namely printing, gunpowder, and the magnet. For these 3 have changed the whole face and stage of things throughout the earth, the first in literature, the second in warfare, the 3rd in navigation; whence take followed innumerable changes; insomuch that no empire, no sect, no star, seems to have exerted greater power and influence in human affairs than these 3 mechanical discoveries."[eight]

Including Marx's comments:

"Gunpowder, compass, and printing-these are the three major inventions that foretell the arrival of bourgeois society. Gunpowder blasted the knight class to pieces, the compass opened the world market and established colonies, and printing became a tool of Protestantism. In full general, information technology has become a means of scientific renaissance, and has become the almost powerful lever to create the necessary preconditions for spiritual development."[9]

Then, British Sinologist Medhurst pointed out:

"The Chinese people's genius for inventions has manifested in many aspects very early. The three Chinese inventions (navigation compass, printing, gunpowder) take provided an boggling impetus to the development of European civilization."[10]

Joseph Edkins, a Chinese missionary and sinologist, was the kickoff to add papermaking to the iii major inventions mentioned above, and in comparison Japan and Red china he noted that "we must ever remember that they (significant Japan) have no such remarkable inventions as printing, papermaking, the compass, and gunpowder."[11]

Papermaking [edit]

Hemp wrapping paper, China, circa 100 BC

Papermaking has traditionally been traced to China about Advertizement 105, when Cai Lun, an official fastened to the Majestic courtroom during the Han Dynasty (202 BC – AD 220), created a sheet of newspaper using mulberry and other bast fibres forth with fishing internet, old rags, and hemp waste.[12] However, a recent archaeological discovery has been reported from Gansu of paper with Chinese characters on it dating to eight BC.[xiii]

While paper used for wrapping and padding was used in Red china since the 2nd century BC,[xiv] paper used as a writing medium simply became widespread by the 3rd century.[fifteen] Past the 6th century in China, sheets of paper were beginning to be used for toilet newspaper as well.[xvi] During the Tang Dynasty (618–907) paper was folded and sewn into square numberless to preserve the season of tea.[14] The Song Dynasty (960–1279) that followed was the first government to issue paper currency.

Before paper was invented, the ancient Chinese carved characters on pottery, animal bones and stones, cast them on bronzes, or wrote them on bamboo or wooden strips and silk fabric. These materials, however, were either likewise heavy or besides expensive for widespread utilise. The invention and use of paper brought about a revolution in writing materials, paving the way for the invention of printing engineering in the years to come.[17]

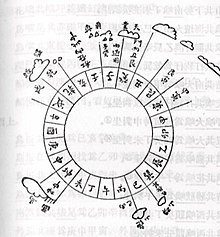

Compass [edit]

Diagram of a Ming dynasty mariner's compass

The compass in the Iv Great Inventions was formerly the compass of ancient China. Information technology is a kind of management-indicating tool, which is widely used in navigation, field exploration and other fields. In ancient times, it had a profound influence on trade, state of war and cultural exchange.

The compass's origins may be traced dorsum to the Warring States Period (476–221 BC), when Chinese people utilized a device known as a si nan to point in the right direction.

During the early Song Dynasty, a spherical compass with a small needle made of magnetic steel was created after steady development. The piddling needle has one end pointing southward and the other pointing north. During the Northern Vocal dynasty (960–1127), the compass was brought to the Arab world and Europe.

People relied on interpreting the positions of the sun, moon, and pole stars to tell directions on open up ocean or new area before the discovery of the compass. When the weather was gloomy or severe, traveling was difficult.

A lodestone compass was used in Communist china during the Han Dynasty between the 2d century BC and 1st century Advertisement, where it was called the "south-governor" (sīnán 司南 ).[18] The earliest reference to a magnetic device used for navigation is in a Song Dynasty volume dated to 1040-1044, where there is a clarification of an iron "south-pointing fish" floating in a bowl of water, aligning itself to the south. The device is recommended as a means of orientation "in the obscurity of the night."[19] The first suspended magnetic needle compass was written of by Shen Kuo in his book of 1088.[20]

According to Needham, the Chinese in the Vocal Dynasty and standing Yuan Dynasty did make use of a dry out compass.[21]

The dry compass used in Communist china was a dry out suspension compass, a wooden frame crafted in the shape of a turtle hung upside down past a board, with the lodestone sealed in by wax, and if rotated, the needle at the tail would always point in the northern cardinal direction.[21] Although the 14th-century European compass-card in box frame and dry pin needle was adopted in China after its utilise was taken past Japanese pirates in the 16th century (who had in turn learned of information technology from Europeans), the Chinese design of the suspended dry out compass persisted in use well into the 18th century.[22]

People could readily locate a direction when sailing on large oceans and exploring new surface area with the creation of the round compass, which led to the discovery of the New World[ citation needed ] and the development of sailing ships.

Gunpowder [edit]

Originally, gunpowder was used to make fireworks for festivals and major events. It was afterwards utilized as an explosive substance in cannons, fire-arrows, and other armed forces weapons. During the Song and Yuan dynasties (960–1368), gunpower was in loftier demand due to numerous battles and the development of mass industry.

Gunpowder was invented in the 9th century by Chinese alchemists searching for an elixir of immortality.[23] By the fourth dimension the Song Dynasty treatise, Wujing Zongyao (武经总要), was written by Zeng Gongliang and Yang Weide in 1044, the various Chinese formulas for gunpowder held levels of nitrate in the range of 27% to 50%.[24] Past the end of the twelfth century, Chinese formulas of gunpowder had a level of nitrate capable of bursting through cast iron metal containers, in the form of the earliest hollow, gunpowder-filled grenade bombs.[25]

In 1280, the flop shop of the large gunpowder arsenal at Weiyang accidentally caught fire, which produced such a large explosion that a team of inspectors at the site a week afterward deduced that 100 guards had been killed instantly, with wooden beams and pillars blown sky loftier and landing at a distance of over 10 li (~2 mi or ~3 km) abroad from the explosion.[26]

Past the time of Hanzo Yu and his Huolongjing (which describes military applications of gunpowder in groovy detail) in the mid-14th century, the explosive potential of gunpowder was perfected, as the level of nitrate in gunpowder formulas had risen to a range of 12% to 91%,[24] with at to the lowest degree half-dozen different formulas in employ that are considered to accept maximum explosive potential for gunpowder.[24] Past that time, the Chinese had invented how to create explosive round shot by packing their hollow shells with this nitrate-enhanced gunpowder.[27] An excavated trove of early Ming land mines showed that corned gunpowder was present in Communist china by 1370. There is evidence suggesting that corned powder may have been used in East Asia as early as the thirteenth century.[28]

Printing [edit]

During the Tang Dynasty, printing was created in China (Advertizement 618-906). The get-go mention of printing is in an AD 593 imperial prescript by the Sui Emperor Wen-ti, who mandates the printing of Buddhist pictures and scriptures.

Woodblock printing [edit]

Blocks made from wood were used in the oldest blazon of Chinese printing. Printing textiles and reproducing Buddhist scriptures were too washed using these blocks. Short religious writings were carried as charms in this fashion.

The Chinese invention of woodblock printing, at some point earlier the offset dated book in 868 (the Diamond Sutra), produced the world's offset print civilization. According to A. Hyatt Mayor, curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, "it was the Chinese who really invented the ways of communication that was to dominate until our age."[29] Woodblock printing was better suited to Chinese characters than movable blazon, which the Chinese besides invented, merely which did not replace woodblock printing. Western press presses, although introduced in the 16th century, were not widely used in China until the 19th century. China, along with Korea, was one of the terminal countries to adopt them.[30]

Woodblock printing for textiles, on the other manus, preceded text printing by centuries in all cultures, and is offset establish in China at around 220.[31] It reached Europe by the 14th century or earlier, via the Islamic globe, and by around 1400 was beingness used on paper for former master prints and playing cards.[32] [33]

Moveable type printing [edit]

Press in Northern China was further advanced past the 11th century, every bit it was written by the Vocal Dynasty scientist and statesman Shen Kuo (1031–1095) that the common artisan Bi Sheng (990-1051) invented ceramic movable type printing.[34] Then at that place were those such as Wang Zhen (fl. 1290-1333) who invented respectively wooden type setting, which afterwards influenced developing metal moveable type press in Korea (1372-1377). Movable blazon printing was a tedious process if 1 were to assemble thousands of individual characters for the printing of simply one or a few books, merely if used for printing thousands of books, the process was efficient and rapid enough to exist successful and highly employed. Indeed, at that place were many cities in Cathay where movable type printing, in wooden and metallic form, was adopted by the enterprises of wealthy local families or large private industries. The Qing dynasty court sponsored enormous press projects using woodblock movable type printing during the 18th century. Although superseded past western press techniques, woodblock movable blazon press remains in use in isolated communities in Red china.[35]

Assay [edit]

Although Chinese culture is replete with lists of significant works or achievements (due east.chiliad. 4 Bully Beauties, Four Dandy Classical Novels, 4 Books and Five Classics, etc.), the concept of the Four Great Inventions originated from the West, and is adapted from the European intellectual and rhetorical commonplace of the Three Great (or, more properly, Greatest) Inventions.[ citation needed ] This commonplace spread rapidly throughout Europe in the 16th century and was appropriated simply in modernistic times by sinologists and Chinese scholars. The origin of the Three Groovy Inventions—these being the printing printing, firearms, and the nautical compass—was originally ascribed to Europe, and specifically to Frg in the case of the press press and firearms. These inventions were a badge of honour to modern Europeans, who proclaimed that in that location was nothing to equal them amid the aboriginal Greeks and Romans. After reports by Portuguese sailors and Spanish missionaries began to filter back to Europe kickoff in the 1530s, the notion that these inventions had existed for centuries in Cathay took hold. By 1620, when Francis Salary wrote in his Instauratio magna that "press, gunpowder, and the nautical compass . . . have altered the face and state of the world: beginning, in literary matters; second, in warfare; 3rd, in navigation," this was hardly an original idea to most learned Europeans.[36]

In the 19th century, Karl Marx commented on the importance of gunpowder, the compass and printing, "Gunpowder, the compass, and the press press were the three swell inventions which ushered in conservative lodge. Gunpowder blew up the chivalry form, the compass discovered the world market and found the colonies, and the press press was the musical instrument of Protestantism and the regeneration of science in general; the most powerful lever for creating the intellectual prerequisites."[37]

Western writers and scholars from the 19th century onwards commonly attributed these inventions to China. The missionary and sinologist Joseph Edkins (1823–1905), comparing People's republic of china with Nippon, noted that for all of Japan's virtues, it did non brand inventions equally significant as paper-making, printing, the compass and gunpowder.[38] Edkins' notes on these inventions were mentioned in an 1859 review in the journal Archives, comparing the gimmicky science and engineering science in People's republic of china and Nippon.[39] Other examples include, in Johnson'south New Universal Cyclopædia: A Scientific and Popular Treasury of Useful Cognition in 1880,[40] The Chautauquan in 1887,[41] and by the sinologist, Berthold Laufer in 1915.[42] None of these, however, referred to four inventions or called them "bang-up."

In the 20th century, this list was popularized and augmented by the noted British biochemist, historian, and sinologist Joseph Needham, who devoted the subsequently part of his life to studying the science and civilization of aboriginal China.[22]

Recently, scholars accept questioned the importance placed on the inventions of paper, press, gunpowder, and the compass. Chinese scholars in item question if too much emphasis is given to these inventions, over other pregnant Chinese inventions. They accept pointed out that other inventions in China were peradventure more sophisticated and had a greater bear upon inside China.[7]

In the chapter "Are the 4 Major Inventions the Most Of import?" of his volume Aboriginal Chinese Inventions, Chinese historian Deng Yinke writes:[43]

The four inventions do not necessarily summarize the achievements of scientific discipline and applied science in ancient China. The four inventions were regarded as the near important Chinese achievements in science and technology, simply because they had a prominent position in the exchanges between the East and the Westward and acted as a powerful dynamic in the evolution of capitalism in Europe. As a matter of fact, ancient Chinese scored much more than the four major inventions: in farming, iron and copper metallurgy, exploitation of coal and petroleum, mechanism, medicine, astronomy, mathematics, porcelain, silk, and wine making. The numerous inventions and discoveries greatly advanced China's productive forces and social life. Many are at least every bit important as the iv inventions, and some are even greater than the four.

Cultural influence [edit]

In 2005, the Hong Kong postal service created a special stamp issue that featured the Iv Great Inventions.[44] The stamp series was first issued on Baronial eighteen, 2005 during a anniversary where an enlarged kickoff 24-hour interval cover was stamped.[45] Allan Chiang (Postmaster Full general) and Prof. Chu Ching-wu (President of the Hong Kong University of Science and Applied science) marked the issue of the special stamps by personally stamping the first day cover.[45]

The Four Great Inventions was featured as one of the master themes of the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics.[46] Newspaper making was represented with a dance and an ink cartoon on a huge piece of paper, press by a gear up of dancing printing blocks, a replica of an ancient compass was showcased, and gunpowder past the extensive firework displays during the ceremony. A survey by the Beijing Social Facts & Public Opinion Survey Center plant that Beijing residents institute the program on the 4 Great Inventions the most moving function of the opening ceremony.[47]

Other important inventions [edit]

Other significant innovations were made, all the same they are non included among the elevation four. Silk and porcelain were the nearly important for world profit and the growth of the various empires' economic system.

They were valuable commercial items exchanged along the Silk Route routes, and when the processes for producing them were understood in Europe and the Islamic world, large businesses grew in both.

Run across also [edit]

- Dream Pool Essays

- History of science and technology in China

- Listing of Chinese inventions

- Scientific discipline and applied science of the Han Dynasty

- Technology of the Song Dynasty

Notes [edit]

- ^ "The Four Great Inventions". People's republic of china.org.cn. Retrieved 2007-eleven-eleven .

- ^ "Iv Great Inventions of Ancient Mainland china -- Compass". ChinaCulture.org. Archived from the original on 2007-04-09. Retrieved 2007-eleven-11 .

- ^ "Four Great Inventions of Ancient China -- Gunpowder". ChinaCulture.org. Archived from the original on 2007-08-28. Retrieved 2007-11-11 .

- ^ "Four Great Inventions of Ancient Red china -- Paper". ChinaCulture.org. Archived from the original on 2007-x-xviii. Retrieved 2007-11-11 .

- ^ "Four Neat Inventions of Ancient China -- Printing". ChinaCulture.org. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2007-11-xi .

- ^ "Four Smashing Inventions of Ancient China". 2004-10-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-condition (link) - ^ a b "Do Nosotros Demand to Redefine the Height Iv Inventions?". Beijing Review (35). 2008-08-26. Retrieved 2008-11-04 .

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia, Schirokauer, Conrad; Hansen, Valerie. "China in 1000 CE".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The people are the creators of history". iNEWS. 2021-12-02.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Medhurst, W.H. (1838). China, its Country and Prospects. pp. 101–107.

- ^ Edkins, Joseph (1884). Religion in China. London. p. 2.

- ^ "Papermaking". Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved 2007-xi-11 .

- ^ "Globe Archaeological Congress eNewsletter". 2006-08-xi. Archived from the original on 2007-11-06. Retrieved 2007-eleven-11 .

- ^ a b Needham, V 1, p. 122

- ^ Needham, 5 one

- ^ Needham, 5 ane, p. 123

- ^ "Iv Slap-up Inventions of China". Embassy of the People'south Republic of Communist china in Antigua and Barbuda. Nov 12, 2013. Archived from the original on 2022-03-17.

- ^ Merrill, Ronald T.; McElhinny, Michael W. (1983). The World's magnetic field: Its history, origin and planetary perspective (2nd printing ed.). San Francisco: Bookish printing. p. ane. ISBN0-12-491242-7.

- ^ Shu-hua, Li (July 1954). "Origine de la Boussole 11. Aimant et Bousso". Isis. Oxford: Oxford Pupil Publications. 45: 175–196. doi:10.1086/348315. S2CID 143585290.

- ^ Kreutz, Barbara Thousand. (July 1973). "Mediterranean Contributions to the Medieval Mariner'southward Compass". Technology and Culture. 14 (three): 373. doi:x.2307/3102323. JSTOR 3102323. (note 21)

- ^ a b Needham, IV 1, p. 255

- ^ a b Needham, IV one, p. 290

- ^ Buchanan (2006), p. 42

- ^ a b c Needham, V vii, pp. 345

- ^ Needham, V 7, pp. 347

- ^ Needham, V 7, pp. 209-210

- ^ Needham, V 7, pp. 264.

- ^ Andrade (2016), p. 110

- ^ A Hyatt Mayor (1971). Prints and People. Vol. Nos 1-4. Princeton: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN0-691-00326-two.

- ^ McGovern, Melvin (1967). "Early on Western Presses in Korea". Korea Journal: 21–23.

- ^ Shelagh Vainker in Anne Farrer, ed. (1990). Caves of the Thou Buddhas. British Museum publications. p. 112. ISBN0-7141-1447-2.

- ^ A Hyatt Mayor (1971). Prints and People Nos 5-xviii. Princeton: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN0-691-00326-ii.

- ^ Arthur Thou. Hind (1963) [1935]. An Introduction to a History of Woodcut. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 64–127. ISBN0-486-20952-0.

- ^ Needham, 5 1, p. 201.

- ^ Olympics bring unexpected luck to Red china'due south sole hamlet using age-sometime movable-type press, People'southward Daily

- ^ Boruchoff, 2012.

- ^ Marx, Karl. "Segmentation of Labour and Mechanical Workshop. Tool and Machinery". Economic Manuscripts of 1861-63.

- ^ Edkins, Joseph (1859). The religious condition of the Chinese: With observations on the prospects of christian conversion among that people. Routledge-Warnes and Routledge. p. 2.

- ^ Maurice, Frederick Denison, Charles Wentworth Dilke, Thomas Kibble Hervey, William Hepworth Dixon; et al. (1859). The Athenæum: a journal of literature, science, the fine arts, music, and the drama. J. Francis. p. 839.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors listing (link) - ^ Frederick Augustus Porter Barnard, Arnold Guyot (1880). Johnson's New universal cyclopædia: a scientific and popular treasury of useful knowledge ... Vol. 1, Function 2 of Johnson'southward New Universal Cyclopædia: A Scientific and Pop Treasury of Useful Knowledge. A.J. Johnson & Co. p. 924. Retrieved 2011-eleven-28 .

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Theodore L. Alluvion, Frank Chapin Bray, Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle, Chautauqua Institution (1887). The Chautauquan: a weekly newsmagazine, Volume 8. Vol. 8. p. 59. Retrieved 2011-eleven-28 .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ "Some Fundamental Ideas of Chinese Culture, Clark University (Worcester, Mass.) (1915). The Periodical of international relations, Volume 5. p. 171. Retrieved 2011-11-28 .

- ^ Deng (2005), pp. xiv.

- ^ ""Iv Peachy Inventions of Ancient Prc" stamp event". Hongkong Postal service. 2008-xi-twenty. Archived from the original on 27 July 2005.

- ^ a b "Four Bang-up Inventions of Ancient China" Special Stamps Issuing Ceremony Archived 2008-11-twenty at the Wayback Machine, Hongkong Mail service

- ^ Beijing Olympics opening features four inventions of ancient China, China Daily

- ^ "Four great inventions" at Olympic opening warmly-welcomed, People's Daily

References [edit]

- Andrade, Tonio, ed. (2016). The Gunpowder Historic period: Communist china, Military Innovation, and the Ascent of the West in World History. Princeton: Princeton Academy Press.

- Boruchoff, David A. (2012), "The Three Greatest Inventions of Modern Times: An Idea and Its Public", in Hock, Klaus, Gesa; Mackenthun (eds.), Entangled Knowledge: Scientific Discourses and Cultural Departure, Münster: Waxmann, pp. 133–163, ISBN978-3-8309-2729-seven

- Buchanan, Brenda J., ed. (2006). Gunpowder, Explosives and the State: A Technological History. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN0-7546-5259-9.

- Deng Yinke (2005). Ancient Chinese Inventions . Translated past Wang Pingxing. Beijing: China Intercontinental Printing. ISBN7-5085-0837-8.

- Li Shu-hua (1954). "Origine de la Boussole 11. Aimant et Boussole". Isis. Vol. 45, no. two: July. Oxford. pp. 175–196.

- Needham, Joseph (1962). Physics and Physical Technology, Part one, Physics. Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 4. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Needham, Joseph, ed. (1985). Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Part 1, Tsien Hsuen-Hsuin, Paper and Printing. Scientific discipline and Civilisation in China. Vol. 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Needham, Joseph, ed. (1994). Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part vii, Robin D.S. Yates, Krzysztof Gawlikowski, Edward McEwen, Wang Ling (collaborators) Military Technology; the Gunpowder Epic. Science and Culture in Cathay. Vol. 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Inventions Of The 15th Century,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Four_Great_Inventions

Posted by: whitehavager.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Inventions Of The 15th Century"

Post a Comment